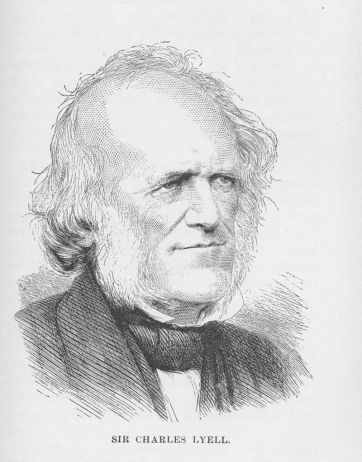

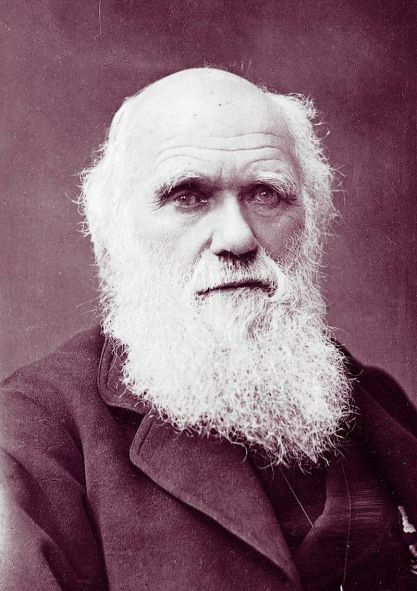

Last week, I told the story of the time Darwin received a harrowing letter from Alfred Russel Wallace. The date was June 18th, 1858, and Darwin had potentially lost his originality. His claim to “discovering” evolution through natural selection–an idea he had been working on for twenty years–had seemingly vanished before his eyes. When I left off, Darwin had forwarded Wallace’s paper to Lyell. So what happened next?

A flurry of letters

On June 25th, Darwin wrote a series of letters that show how stressed and saddened he had become over the situation. The first was a follow up to Lyell (it appears that between June 18-25 Lyell had responded to Darwin’s original letter of panic, though that letter–along with many from this nightmare period–has been lost, a topic I’ll cover in the next post).

In this letter (along with a follow up “P.S.” letter he sent the following day), Darwin defends his scientific priority, detailing the few scholars who did know about Darwin’s work. He informs Lyell that in addition to himself, an American named Asa Gray had read a sketch of natural selection Darwin penned back in 1844. Lyell and Gray are really all Darwin had to support his claim that he had been working on the theory long before Wallace’s letter showed up.

Darwin then asks Lyell what his next steps should be. Should he try to publish now, quickly, even though he had read Wallace’s paper and knows it exists? Is that honorable? Darwin wanted to get something published, but he wanted to know whether or not this was unfair to Wallace (remember, scientific priority through print is an incredibly permanent and important thing!). “If I could honourably publish,” Darwin writes “I would state that I was induced now to publish a sketch,” due to Wallace’s letter. He adds “I should be very glad to be permitted to say to follow your advice long ago given.”

If Darwin was to publish, he could take steps to show that he was not plagiarizing Wallace’s work. He was particularly keen to prove this to Wallace himself. “I could send Wallace a copy of my letter to Asa Gray,” he told Lyell, “to show him that I had not stolen his doctrine.”

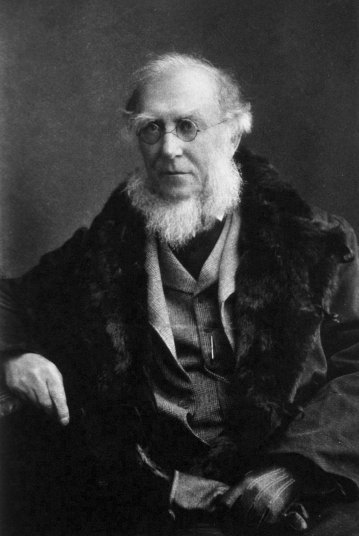

Finally, Darwin asked Lyell to incorporate another friend into the discussion, Joseph Hooker. Hooker, a talented botanist, was a close friend of both men– as well as one of the few others who knew what Darwin had been working on. Darwin wanted Hooker to see Lyell’s response, craft his own response with advice, and forward the entire package back to Darwin. There would be a quorum of scientific men, then, discussing the best approach to handling this tragedy. Once Lyell and Hooker responded, Darwin told Lyell “I shall have the opinion of my two best & kindest friends.”

Complications and a death in the family

An alternative, Darwin thought, was to publish his own work and Wallace’s side by side. But this was complicated, given Wallace’s location. Wallace was still in the Malay Archipelago, collecting butterflies and battling malaria. He had no notion of the chaos he had caused in Britain.

Darwin was worried about going ahead and publishing Wallace’s paper without his consent. Wallace might say “you did not intend publishing an abstract of your views till you received my communication,” Darwin mused to Lyell, “is it fair to take advantage of my having freely, though unasked, communicated to you my ideas, & thus prevent me forestalling you?” We can see that Darwin is attempting to argue both sides, but cannot decide where the lines between priority, honorability, and discovery should be drawn. His concluding sentiment to Lyell is that “first impressions are generally right & I at first thought it would be dishonourable in me now to publish.”

To make matters worse, Darwin’s youngest child, the baby named after himself–Charles Waring Darwin–was gravely ill. He died on Monday, June 28, 1858, the second child Darwin and his wife Emma had tragically lost. “I have had death & illness & misery amongst my children” Darwin wrote.

Lyell and Hooker in action

Lyell and Hooker both acted quickly, revealing the urgency of the situation. By June 29th Darwin had received their responses, they want him to publish right way. Darwin responded to Hooker on the 29th, sounding deflated and defeated. “I daresay all is too late. I hardly care about it,” Darwin wrote.

He did care though, as we can see in the continued steps he took to protect his priority. Darwin forwarded Hooker the precious 1844 sketch. Hooker had made corrections on it back then, so Darwin was allowing him to see, once more, those corrections written in Hooker’s own handwriting- (in case Hooker had forgotten he had reviewed this scientific bombshell). But “I really cannot bear to look at it,” Darwin told Hooker.

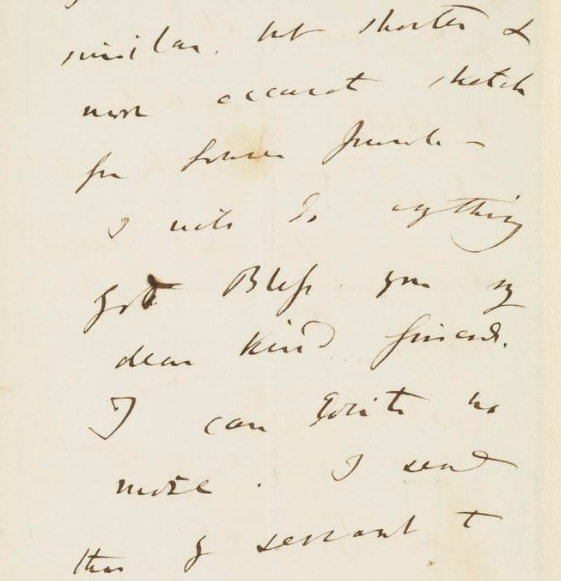

Ultimately though, Darwin did respond to Hooker’s call to publish, saying he could “make a similar, but shorter & more accurate sketch for Linnean Journal,” adding “I will do anything” to protect his ideas. All the while, Darwin clearly felt terrible for involving his friends in this mess, “I will never trouble you or Hooker on this subject again,” he told Lyell. But he needed help getting himself out of it. “Do not waste much time,” Darwin cautioned Hooker; “it is miserable in me to care at all about priority,” he admitted.

Hooker, wikicommons

A few days later, Darwin also reached out to Asa Gray, grasping at straws for any written proof that his idea had preceded Wallace. “If by any chance you have my little sketch of my notions of “natural Selection” & would see whether it or my letter bears any date, I should be very much obliged.” The date would provide further proof that Darwin had come up with this idea before receiving Wallace’s letter. Darwin explains to Gray that “Mr. Wallace…has sent me an abstract of the same theory, most curiously coincident even in expressions. And he could never have heard a word of my views.” Darwin then goes on to explain that the “very brief thing” he had written to Gray was one of the only copies that prove his precedent. “But do not hunt for it,” the ever-polite Darwin wrote.

Part II conclusion, a curiously coincidental nightmare

So here we are, at the end of part II. Nothing is yet resolved, Wallace is still wonderfully oblivious, and Darwin is grief-stricken, panicked, and deflated. He has sent a flurry of letters to his closest friends, begging for advice, and strategies are being devised to protect Darwin’s scientific priority and honorability.

Stay tuned next week for the third and final post on Darwin’s worst nightmare–when the event ultimately comes to a conclusion. In part III, we will the exciting reveal of the concept of natural selection to a captive audience, as well as ask questions about Darwin’s morals and potential deceit. The letters quoted in today’s post are all online, courtesy of the Darwin Correspondence Project: June 25th, June 26th, June 28th, July 4th.

“I will do anything,” Darwin Correspondence Project.

Thanks for the wonderful insightful history!

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Pingback: Darwin’s Worst Nightmare Part III: Conclusion of a Colossal Coincidence | Paige Fossil History

Hello Paige

Nice to see inside thé history through your eyes .

Erratum

In the first lines here you wrote 1958. It is of course a typo, you mean 1858.

Have a nice time

LikeLike

Awesome story! Thanks!

LikeLike