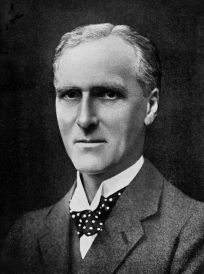

Arthur Keith, autobiography

It is no exaggeration to say that Arthur Keith spent much of his life thinking about skulls. “If after death any image is found engraven on my brain, I am sure it will prove to be that of a human skull,” he declared in his autobiography. “The days I have spent—I almost wrote, wasted—in seeking to wrest from it secrets concerning human evolution are beyond number.” Indeed, Keith was a giant in the science of human origins during the first half of the twentieth century, a central figure in the discussions of famous hominin fossils such as Piltdown, Taung, and many more.

Keith’s Legacy

I spent the better part of October examining Keith’s papers. After the hours spent pouring over his diaries, letters, and skull illustrations, I could not let his death day (January 7, 1955) pass unnoticed. I would like to celebrate his life and work, but how to celebrate a man like Arthur Keith? For me, that is a difficult question. Studying Keith showed me that he was a complex character. Some days I wanted to weep for the man who wrote diary entries about his wife’s ill health and death, after decades of marriage. Other days I was perplexed by his refusal to let go of racist ideas, even after many of his contemporaries had publicly declared race as a social construct not rooted in anatomical fact.

Of course, as a historian, it is my job to not judge Arthur Keith. He was a man of his time, brilliant but complex. But this is my blog, so I can admit here that judgment occasionally seeps in. Back to the question of how to celebrate a man who did so much for the field of paleoanthropology, yet often baffles and frustrates me? By highlighting one simple act that, I think, speaks volumes about his character: Arthur Keith had the courage to admit when he was wrong.

Keith is often remembered for his role in the story of the Taung child. When a much younger scientist, Raymond Dart, presented the shocking fossil of Australopithecus africanus in 1925, Keith’s response was harsh. Keith criticized Dart’s analysis, dismissing the Taung Child as an infant gorilla (rather than a potential human ancestor), and essentially silencing Dart for years. The traits that Dart saw as human-like, Keith argued were just an artifact of the individual’s juvenile age.

As more fossils began to emerge from South African caves over the next two decades, however, Keith’s position became hard to justify. It eventually became clear that the Taung child was not just a young gorilla, but instead a member of a hominin genus Dart had called Australopithecus (meaning southern ape from Africa).

By the time Australopithecines began to be widely accepted in paleoanthropological circles, Arthur Keith was an old man. He had conducted a lifetime of careful analyses, studying countless human skulls and hominin fossils, and advancing knowledge of how humans came to be here. Keith had even been knighted for these efforts. His career was legendary, yet he retained a bit of humility. In a Nature letter to the editor in 1947, Keith wrote–for all the world to see–“I am now convinced … that Prof. Dart was right and that I was wrong.”

This simple phrase may seem like a small gesture, unimportant in the grand scheme of things. But admitting defeat in such a direct, public way is in incredibly difficult thing to do. It is also an act that greatly affects science’s future. Many scientists cling to their original conclusions all the way to their graves. Keith instead took the high road, a move that Dart appreciated–despite the fact that Keith immediately went on to complain about Dart’s naming of the creature. Keith felt that the term Australopithecinæ was too cumbersome, the creatures should instead be named Dartians after their discoverer (an idea that never took hold).

Paleoanthropology is often thought of as a discipline fully of petty feuds between proud, individual scientists. Fossils are often jealously guarded, and new hypotheses are sometimes met with derision. I would like to change that narrative, illustrating that paleoanthropology has also been (at times) a science that progresses through new discoveries, new methods of analysis, and scientists with open minds. When someone like Keith recognizes new evidence, it is not defeat at all, but instead an important step to moving the science forward.

There is much more to Keith’s life and career than his involvement in the Taung story, and I hope in the future to illuminate more aspects of his life and work. But for now, I thought this was a good reminder of humility in the scientific process. What about you all, do you think Keith’s note in Nature was admirable?

Source: Keith, Arthur, “Australopithecinæ or Dartians” Nature 159, 377(15 March 1947) doi:10.1038/159377a0

Keith’s admission of error was certainly a major admission by academic standards. In any normal sense, admission of error is simply part of being an adult, and it’s how people learn; but it doesn’t seem to happen where ego and self-worth are tangled with status in an academic field. No question that the problem dogged paleoanthropology, although I suspect Dart also had a problem because he was an Australian at Oxford (“bloody colonials!” 🙂 ) My own experience of the phenomenon, incidentally, was brought home to me here in NZ a few years ago when our top historian got openly angry and swore at me, live on national radio, merely when my name was mentioned by the interviewer. I’d been through university with him and he knew very well how to contact me, but he never did – just swore and raged to the nation. My cardinal sin was writing a book-length rebuttal of his PhD thesis, which he’d been trading off.

LikeLike

It should be part of any decent [sic] ethical science standard [ https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/doing-good-science/the-ethics-of-admitting-you-messed-up/ ]. But standards is theory, behaviors is practice.

One recent case came to mind: https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/blog/eureka-lab/oops-correcting-scientific-errors . [I have also seen a very thorough debunking of an own paper in a biology blog recently, but can’t find it. Assuming the later result is the correct one, what can one say? It is also very efficient for the persons directly involved, they can get on with their research.]

LikeLike

Yup, that’ll do it. You have my apepacirtion.

LikeLike

Admitting you were wrong is HARD! I realized, some years back, that I had made a mistake in a published paper. (I’m a philosopher, and the paper was in logic: the mistake was in a mathematical proof, so about as clearly identifiable as a mistake as mistakes ever are!) So (honest soul that I am) I wrote a retraction. There was a clear prudential reason for submitting the retraction as soon as possible (better for my reputation to be the person to catch the mistake rather than have it pointed out by a commentator!), and yet… I realized I was procrastinating about sending it off: admitting one is wrong is HARD, and part of me just wanted to avoid doing it!

LikeLike

No qutiseon this is the place to get this info, thanks y’all.

LikeLike